‘Heritage assets’ in Binsted threatened by the Grey route

Highways England has written a ‘Scoping Report’ about the Arundel bypass as part of the planning process.[1] It attempts to give the impression that the Grey route does no damage to Binsted, or other villages, at all, by the use of tendentious language and incorrect facts.[2]

As Highways England point out, heritage assets may be ‘buildings, monuments, sites, places, areas or landscapes. Significance derives not only from a heritage asset’s physical presence, but also from its setting.’ This paper aims to show what Binsted’s heritage assets are under those headings.

A. Buildings

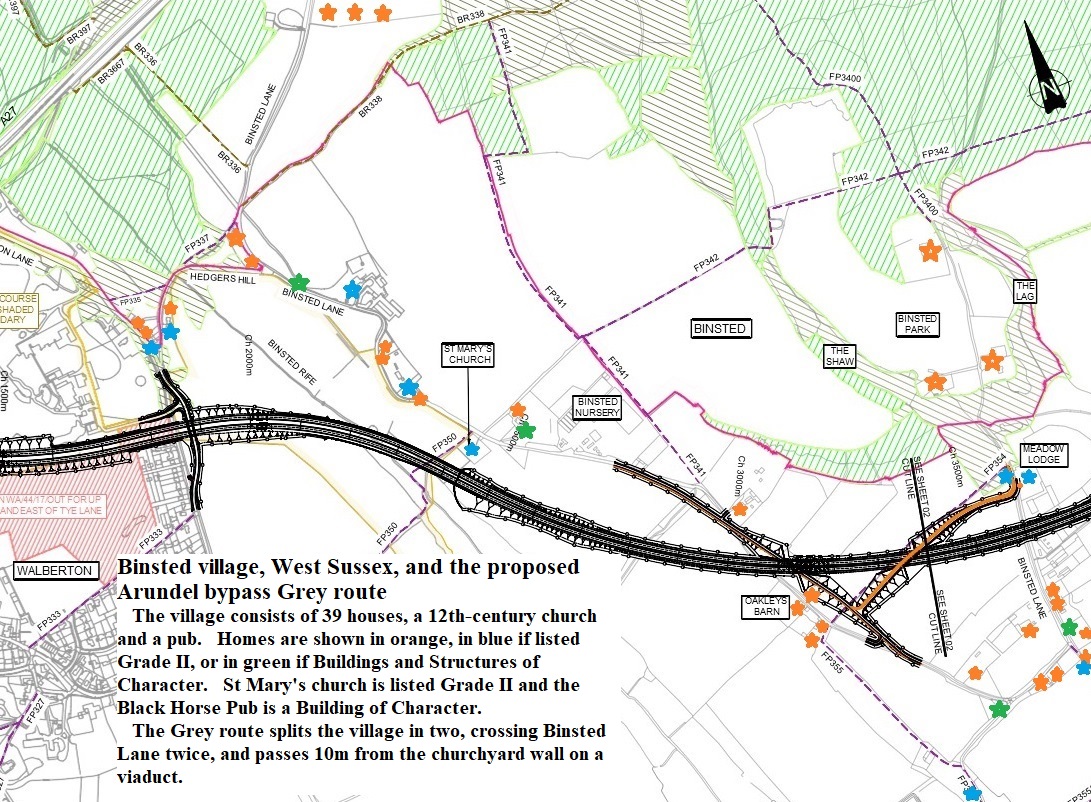

Fig. 1: Buildings in Binsted, West Sussex, and the Grey route

Major error in Highways England’s Scoping Report: it says many times that the Grey route passes ‘south of Binsted’. The Grey route cuts Binsted village in half, crossing its only access lane twice, both times with a high, intrusive overbridge to carry the lane across the new road.

There are 9 Grade II listed buildings in Binsted – 8 houses and St Mary’s Church. In addition, four buildings in Binsted are ‘locally listed’ as ‘buildings or structures of character’, the Old Rectory, Grove Lodge, Bramble Barn and the Black Horse Pub. Individual listed houses and St Mary’s Church would suffer very badly from proximity to the Grey route.

- Meadow Lodge, listed Grade II, would be c. 70m from the Grey route, and one of the two high overbridges needed to raise Binsted Lane over the Grey route would come down in its front garden a few feet from the house.

- Morley’s croft, listed Grade II, would be c.90m from the Grey route, and would also be at the foot of one of the two high overbridges needed to raise Binsted Lane over the Grey route.

- Glebe Cottage, listed Grade II, would be c. 100m from the Grey route.

- Church Farm, listed Grade II, c18 farmhouse, would be c. 200m from the Grey route.

- Swiss Cottage, listed Grade II, would be c. 120m from the Grey route, and very close to the foot of the overbridge needed to raise Yapton Lane over the Grey route.

- Quince Cottage (was Beam Ends), listed Grade II, would be c. 100m from the Grey route. It would also be very close to the foot of the overbridge needed to raise Yapton Lane over the Grey route. Its peaceful outlook over the Binsted Rife Valley would be replaced by a view of the Grey route and Yapton lane passing over it on a high overbridge.

- Thatched Cottage, Listed Grade II, would be c. 300m from the Grey route. It would be separated from the rest of the village by the Grey route.

- Marsh Farm, listed Grade II, Elizabethan farmhouse, would be c. 400m from the Grey route. It would be separated from the rest of the village by the Grey route.

- ‘Buildings of character’ Bramble Barn would be c. 120m from the Grey route and would be separated from the rest of the village.

- ‘Building of character’ Grove Lodge would be c. 200m from the Grey route and would be separated from the rest of the village.

- ‘Building of character’ the Old Rectory, c. 1865, would be 100m from the Grey route, and the church for which it was built would completely lose its significance. See the section on St Mary’s Church below.

- ‘Building of character’ the Black Horse Pub would have its peaceful setting overlooking the Binsted Rife valley destroyed. While the golf course planting might screen the actual road, the noise of a dual carriageway c. 200 metres away would make sitting in the pub garden unpleasant.

- St Mary’s church, listed Grade II, would suffer very badly. The Grey route would be 10m from the churchyard wall, on a raised viaduct, at the level of the top of the wall. The church building would be c. 30m from the Grey route. See more on St Mary’s church below at Section F.

Major error in Highways England’s Scoping Report: it says there are ‘no community facilities alongside the Grey route’. St Mary’s Church is a community facility.

B. Monuments

War Dyke

The Iron Age linear bank and ditch (double in places) known as War Dyke passes through the whole of historic Binsted Parish from north to south. This would be massively affected by the Grey route.

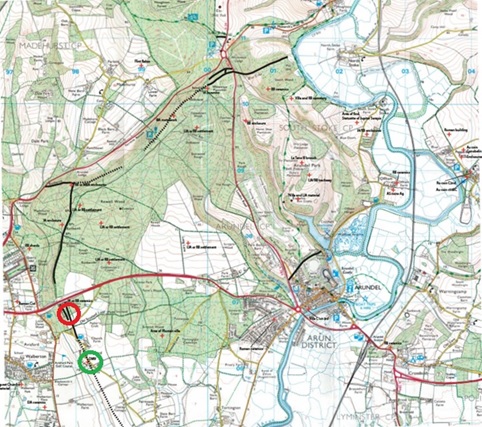

The section through Binsted is part of a larger monument, the northern section of which is a Scheduled Monument (List Entry 1002983). The section through Binsted is demonstrably of equivalent significance to the scheduled part. The Scheduled Monument is known as War Dyke, but the name War Dyke now refers (as used by archaeologists, e.g. David McOmish of Historic England) to the whole of the earthwork, which is thought to have joined loops of the river Arun and tributaries to defend or define an area. See the map of the whole earthwork (below) acquired from David McOmish. The Red ring indicates the section threatened by the previous Arundel Bypass Preferred Route (2018). The Green ring indicates part of the section at St Mary’s Church, Binsted, threatened by the Grey route, though the Grey route would also destroy remnants of War Dyke in the field to the south.

Fig. 2: Map of War Dyke. The solid black northern section is a Scheduled Monument.

The Grey Route would pass St Mary’s Church on a viaduct, at the level of the top of the churchyard wall and ten metres from it. This would obscure or destroy the large bank directly underneath St Mary’s Church and churchyard, which may be part of War Dyke. See photograph at Fig. 3.

Fig. 3: The impressive earth bank, possibly part of War Dyke, beneath St Mary’s Church, Binsted

C. Sites

The Moot Mound

The recently identified Moot Mound, c. 500m north of St Mary’s Church, was sited up against the bank of War Dyke, probably to gain authority from it as an ‘ancient monument’.

Binsted was the meeting place of the Binsted Hundred (unit of countryside administration) before the Norman Conquest. In 2017 the likely site of the meeting place, or Moot Mound, was identified.[3] The arguments included the shape and size of the domed hillock, its position on the edge of thesteep side of Binsted valley, the ‘hollow way’ running up the hill beside it, the nearness of the Iron Age earthwork, the nearness of several Parish boundaries, the existence of routes to it such as the mediaeval track of Scotland Lane, and the evidence of place names (Hundredhouse Copse, Hundredhouse Field). It was probably also the meeting place of the Aves Court connected with Arundel Forest, organising the pasturing of animals in the Forest area (not all wooded).

As Historic England states of Alstoe Moot Mound: ‘All well preserved or historically well documented moot mounds are identified as nationally important’. The identification of the Moot Mound means that Binsted is not just a farming landscape, but also a ‘landscape of governance’. Routes such as Scotland Lane, an ancient wide track through Binsted Woods, between earth banks, can now be seen as leading to the Moot Mound. The Iron Age earthwork itself may have been used as an approach path.

The Moot Mound is not in danger from the Grey Route – but the Mound is mentioned here to show that the landscape of Binsted, especially the historic Binsted Parish, has much more significance than at first appears.

The pottery kilns

In the 13th and 14th centuries an important pottery industry was located in Binsted. Its ware, known as ‘Binsted ware’, as well as roof tiles, included pottery such as jugs with faces.

(a) Mediaeval pottery and tile kiln in the garden of ‘Glentham House’, Binsted, SU 97937 06514

Excavated in 1967 by Con Ainsworth (K.J.Barton, Mediaeval Sussex Pottery, 1979, pp 170-179). The material from this excavation is held at Worthing Museum. Over the past 2-3 years Worthing Archaeological Society (WAS) have been undertaking the task of cataloguing in detail the finds from this excavation.

(b) Tile kiln site in field opposite Black Horse Pub, Binsted, NGR SU 98037 06611.

There were two separate archaeological projects undertaken in this field north of Church Farm, Binsted: a Test Pits and Surface Collection Survey (1999-2003) and the Tile Kiln excavation (2005).

Articles in the WAS Journal provide a high-level overview. WAS Journal, vol. 3 No. 7 (Winter 2006) contains an article (pages 8-13) by G. Hennings of the field work undertaken in the period 1999-2003. WAS Journal, vol. 3 No. 5 (Summer 2005) contains a non-technical short article (pages 5-6) summarising the 2005 excavation, and also a short article (page 7) based on Con Ainsworth’s notes describing the structure excavated in 1967.[4] See also Medieval Archaeology vol. XI (1967).

Like the Moot Mound, the pottery kilns – still in good condition under the ground – show that Binsted’s landscape has much more significance than at first appears. The industry was intricately linked to the landscape’s characteristics: the presence of clay, large woodlands providing fuel, and the Binsted Rife for transporting the products.

D. Places

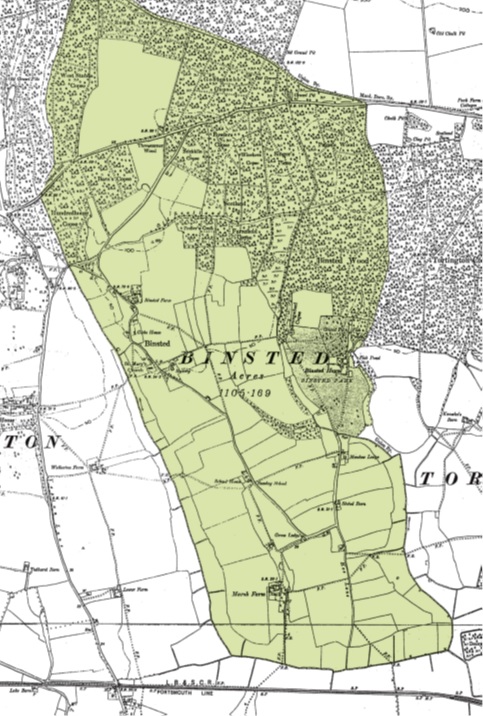

Binsted is a historic independent parish and settlement dating back to Anglo-Saxon times.

Fig. 4: Map of Binsted Parish (in green), 1880.

All the different kinds of land needed for farming – woodland, hedges, arable, pasture, meadow, marsh, watercourses, ponds, claypits, sandpits - are included in the one parish, as they were in many other parishes. This longitudinal layout made for fair use of the varied landscape and geology of the gentlest slopes at the foot of the South Downs. Its one winding lane, bending round in a U-shape, connected the spread-out buildings and gave access to the different types of land. Binsted was joined to Walberton parish in 1983.

Binsted never became a ‘nucleated’ village with a centre. Nucleation happened in the 7th and 8th centuries, so the parish’s unchanged layout is very old and gives a sense of looking back in time. It is a refuge from the modern world. Hence it is a favourite place for many people to walk, especially as half of the old Parish is in the National Park.

Binsted was isolated. The lane does not connect with the outside world at all in the southern part of the parish. Hoe Lane, at the south end of the parish, was on a peninsula in the marshes – a Hoe like Plymouth Hoe. Binsted was self-sufficient. It had its own church from the 12th century, and its own poorhouse next to the church from the 18th century. Taxes were collected since Elizabethan times and used to support the poorest inhabitants.

The Grey route would take away the fundamental significance of Binsted as a place, by destroying its unity, isolation, peacefulness, beauty, and sense of looking backwards in time. The Grey route would also take away the fundamental significance of the 9 listed buildings, as parts of an ancient, spread-out settlement, and ‘powerful reminders of our history and the life and work of earlier generations’ (from Arun District Council’s description of listed buildings).

E. Landscapes

Binsted’s landscape

Binsted’s landscape is very varied. The massive woods (Binsted Woods, 100 ha, part of the Binsted Wood Complex Local Wildlife Site) are its most obvious feature. They consist of 20 named woods, and the edges of the woodland are intricate, with several small fields or ‘assarts’ taken out of the woodland when it was common land. Its fields vary from the two large, central fields of the historic parish, which were farmed in strips by the whole community, to the historic small fields further south in the parish, and small meadows and pastures in the marshy south.

Part of the historic Binsted parish lies north of the A27 and this is very different again. The large worked out sandpit (used for 4 by 4 sport) is part of the same ‘raised beach’ formation as that in which remains of the Boxgrove humans, dating to half a million years ago, were found in the 1990s. There is more woodland, within which are Iron Age enclosures or settlements, part of the area that was ‘enclosed’ by War Dyke.

Binsted Rife valley

The Binsted Rife valley is a steep-sided valley, dramatic north of the A27, and shallower south of the A27. From the A27 south, it has a chalk stream, and its lower reaches are a rare habitat, a ‘Flushed Fen’, one of only two in coastal West Sussex. The steep valley is thought by geologists to have been formed by a ‘melting event’ at the end of the last Ice Age, some 12,000 years ago. Its steep sides were used by the Iron Age monument builders as part of their defence, by building a bank and ditch on the lip of the valley.

The significance of the valley, with its links to the Ice Age, the Iron Age monument, the Moot Mound, the pottery kilns, and 12th-century St Mary’s Binsted, would be severely damaged by the Grey route.

F. St Mary’s Church, Binsted (listed Grade II)

The church’s setting, function, and significance for both local people and visitors from further afield, would all be destroyed by the Grey route.

(a) Church services

Services at the church (part of an ecclesiastical parish with St Mary’s Walberton) happen monthly and on major feasts such as Easter and Christmas. On Rogation Sunday there is a pilgrimage across the Binsted Valley from Walberton with singing by the church choir, which serves both churches. People come to these services partly because of the open, beautiful, peaceful setting of the church on the lip of the steep Binsted valley, with views up and down the valley and across fields to the huge mass of Binsted Woods. If the Grey route was built they would cease to come and the church would be likely to be deconsecrated. It would lose its central function as a church.

(b) The Church’s significance to the village community

Many of Binsted’s past inhabitants are buried in Binsted churchyard. Their families visit the churchyard to remember them and tend the graves. Michael Wishart (1928-96), part of the artistic Binsted family stemming from his mother, Lorna Wishart, describes the significance of Binsted churchyard well in his memoir ‘High Diver’ (London, 1977): ‘As far back as I can remember, certainly before I could speak, I loved to draw and paint, in all their seasonal change, our fields, our parks, our hedges; brooks; barns; trees; and our skies. Of all places to spend these enchanted hours, I preferred our graveyard. It was hardly larger than a more temporary dormitory. I would seat myself against its southern wall, warm in the sunshine, where the corpses of old labourers, some of whom I had known and loved, threw up an abundance of violets of both varieties, scattered rugs of purple and white’ (p. 21). His grave, with a quotation from the poet Henry Vaughan, is near the church porch in St Mary’s graveyard, marked with rose bushes.

(c) Binsted Arts Festival and Strawberry Fair

Binsted church is central to the village community in other ways too: it is the venue for the Binsted Arts Festival, which has taken place in June for the four years 2015-2019;[5] and it is the mainspring of the Binsted Strawberry Fair, which has been held every year for 32 years in the nearby fields and barn to raise money for its fabric. This activity involves many of the villagers and brings the community together. All this would cease if the Grey route was built – not just because the church would no longer be a beautiful venue for events, but also because they Grey route would pass very close to the barn and fields where the Fair is held, destroying its appeal as a country fair on the edge of the South Downs National Park.

The Strawberry Fair, the main fund-raising event for the church, is run by Friends of Binsted Church. In 2000 they published ‘Binsted and Beyond’, a Millennium Book about the village, with a Lottery Fund grant. The book (as a pdf file), and much more about Binsted’s people, art and writing, can be found on www.binsted.org-prose.

(d) The church’s significance to visitors: the British Pilgrimage Trust

The church and its setting are of value not just to the village which it has served for centuries, but to people who visit it for its peace and quiet and the views, or as a sacred place in a more general way. The British Pilgrimage Trust, which has rediscovered the ‘Old Way’, a pilgrimage route from Southampton to Canterbury, gives a route via Binsted church as part of the route:[6]

Fig. 5: British Pilgrimage Trust map showing Binsted church as part of the ‘Old Way’ route.

The Old Way is shown on the Gough Map of c. 1360. It has been revived by the Trust, along with many other pilgrim routes. Alternative routes are given for parts of the route both to avoid over-use and to give opportunities to enjoy more of the still-existing sacred places along the route. Binsted is part of one of these alternative routes.

(e) The church’s architectural importance

Binsted church is listed Grade II and an application is underway to raise its listing to Grade II*, as the excellent quality of its restoration in 1868 has not been sufficiently recognised. The application was accompanied by an article by historian Martin Jones. Below are some quotations from his article:

‘The importance of St Mary’s Binsted

‘For a small single cell church, St Mary’s punches well above its weight. Historically, it holds unusual evidence of the violence of the Reformation and Victorian industrial technology. Architecturally, its Romanesque font and wall painting fragments are important in their own right while the complex influences they illustrate add additional significance.

‘…The 1867-1869 restoration encapsulates perfectly the ideas of Sir Thomas Graham (“Oxford”) Jackson RA (1835-1924), a major later Victorian / Edwardian architect whose work is now increasingly being appreciated,’ in particular his ‘Ruskin-influenced working credo that architects are artists, that the arts must be reunited and that craftsmanship must be revived. Everything was a bespoke design by Jackson and, apart from a chancel screen, everything survives intact.

‘…The glass chancel pavement speaks of the love for industrial innovation so central to the Victorian world view. …Jackson was among its earliest champions and at Binsted in 1869 was the first to use it as flooring.’

‘…St Mary’s is not the very ordinary small rural parish church of West Sussex it may seem. Historically and architecturally, it is an undervalued heritage asset that provides material evidence for significant parts of England’s history. In turn, the way these tie this church into the narrative of England’s past establishes valuable meaning for the local community. St Mary’s Binsted is special.’

Conclusion

The total historic significance of Binsted as a place, as a unified, self-sufficient parish for centuries, with its interlinked steep valley, Moot Mound, Iron Age monument, pottery kilns and special 12th century church, would be very badly damaged by the Grey route.

The Grey route amounts to the destruction of a historic village and parish.

[2] Walberton Parish Council’s critical comment on the Scoping Report highlights many of these errors and can be seen at https://www.walberton-pc.gov.uk/a27/Arundel_Bypass.aspx.

[3] Emma Tristram, ‘Identifying the meeting place of Binsted Hundred, near Arundel, West Sussex’, Sussex Archaeological Collections, 155, 2017. The article is available on https://arundelbypass.co.uk/_app_/resources/documents/www.arundelbypass.co.uk/ABNC%20Supplement%202017%203.1%20Binsted%20Hundred%20Meeting%20Place.pdf, with a map and LiDAR imagery.

[4] The WAS journal is available on www.worthingarchaeological.org under ‘Archive’.

[5] The festival’s fifth year in 2020 was planned, programme agreed and about to be printed, but had to cancel because of Covid.