People from the Past

This website is a tribute to the people who live here, and to all our friends and neighbours. It does give some insights as to how we stay together as a village, and retain our identity. But writing too directly about the people who live here today would risk intruding on privacy or seeming to boast about our community. Instead we will on this page offer some points of contact with a variety of different people who have lived here in the past - in whose footsteps all, who live in or come to Binsted today, are walking.

... on whose shoulders we stand

Binsted's demographic, along with that of most rural communities, has changed over the last 50 or so years. In 1948, when Arthur Wickstead first lived at the Pub, ‘darts were all the go, and there were enough farm workers on Wishart’s farm to make two teams of eleven players’. Now far fewer of the village’s inhabitants work on the land, as the farm is mostly arable and highly mechanised. In addition to the farm there are smallholdings, sheep fields and horse paddocks. Also Binsted Nursery which produces herbs and other garden plants for sale to garden centres (and at the village's traditional Strawberry Fair ).

The advent of the car, the telephone and the computer brought professionals into what were once farm cottages or farm buildings: art, writing, architecture, music, photography, health, insurance, law, antiques, and house conversion are all fields in which recent inhabitants have laboured. Some people who work in the arts have turned to seasonal work on the nursery for supplementary income. In addition to work in farming and horticulture and smallholdings Binsted provides employment opportunities in rural businesses such as Bee Bee Kennels, the pub, the B&B, and farm vehicle hire.

Some houses in Binsted that were modest dwellings have been expanded or replaced by much larger ones, and some redundant farm barns have been turned into beautiful houses. Binsted is a desirable place to live and so house prices are high. But, thanks to the Wishart family's retention of Church Farm's farmworker cottages for letting, Binsted still has a proportion of more affordable rented dwellings, which enable our community to thrive with diversity.

A community exists in the here and now: it also exists over time. To live in or to explore Binsted, whose landscape features still reflect so much of the lives of those on whose shoulders we stand, is, consciously or unconsciously, to connect with Binsted's people from the past. The selections from 'Binsted and Beyond' below came out of the Binsted Book Group's exploration of those connections in 2000-2002.

People in the Past - from 'Binsted and Beyond'

CONTENTS

The Wisharts, by Binsted farmer and landowner Luke Wishart

Isaac Rawlins: a sad tale, by John Heathcote, former Parish Clerk

‘Binsted is on strike’: 1937

A planning battle from the past, which gives us a rich description of Binsted in the 1930s and some of its personalities, is introduced with these words in the Southern Weekly News, Saturday, 22 May, 1937.

It has been waged for four years and it will go on to the bitter end…Binsted, quiet Sussex backwater, tiny village of twisting lanes, trim hedgerows, is on strike…Binsted people mean to fight to keep the name of Binsted alive, to continue their struggle now waged for four years against the West Sussex County Council.

It was in 1933 that the County Council issued the order that the parish of Binsted should be added to the parish of Tortington, a village three miles away. For four years Binsted has refused to ackowledge this change, has stuck more firmly to its own village life, ignored sleepyeyed Tortington even more than Tortington ignores Binsted.

Binsted people will not walk to Tortington for a Parish meeting. Tortington will not come to Binsted. Attempts made to hold a meeting on neutral ground has failed because both sides, by mutual consent, adjourn the meeting almost before it begins, make no decisions.

They call it a strike in Binsted, a strike that has been waged for years but today is reaching a climax. Both the Rector, the Rev. William Drury, and Mr S.H.Upton, genial farmer whose family has farmed on the land in Binsted since 1500, told me that it was a strike – and a strike to the bitter end.

The Rector was indignant. As he put it in the article:

‘Fancy asking our people to walk three miles to a parish meeting! ... It is a matter I am very hot about. The real union would be if Arundel took over Tortington and Binsted was joined to Walberton [as eventually happened in the 1980s] … We used to enjoy our parish meetings so much, too. We could all meet and see each other and talk over matters. Now all that is lost.’

Mr Upton is quoted as giving some good reasons why the two parishes do not blend.

‘Now, Binsted and Tortington have no common interests. Take the Coronation: Binsted had its own show, a great show. We collected £46, had fireworks and plenty of prizes. Because the weather spoilt part of the show on Wednesday we had another Coronation Day last Saturday – with another supper, more fireworks: the whole programme over again! We had a grand time. ... We in Binsted have our own farms and holdings and we are proud of our inheritance. We strongly object to being taken over like this; we refuse to be obliterated. So we are on strike and we refuse to do anything.’

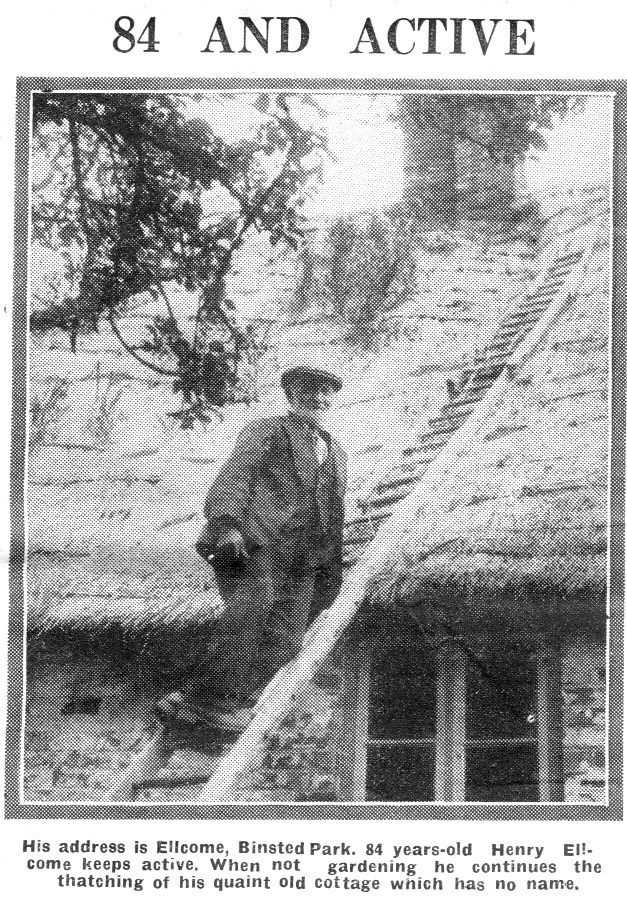

An inset describes Henry Ellcombe, aged 84, of Binsted Park. He lives in ‘a thatched house with no name’ (the house in the Park known earlier as Kent’s cottage, now replaced with a modern house), and thatches it himself. ‘If you want to write to Harry you just put ‘Henry Ellcombe, Binsted Park’. “That’ll find me,” he said with a grin. “Everyone knows me around here.”’

An inset describes Henry Ellcombe, aged 84, of Binsted Park. He lives in ‘a thatched house with no name’ (the house in the Park known earlier as Kent’s cottage, now replaced with a modern house), and thatches it himself. ‘If you want to write to Harry you just put ‘Henry Ellcombe, Binsted Park’. “That’ll find me,” he said with a grin. “Everyone knows me around here.”’The article returns to Mr Upton, to describe the contents of an old chest the reporter is shown. ‘Parish records of Binsted’ are described, possibly the ‘Poor Books’ now in the Record Office, which were donated by him. Also ‘Famous old documents of a greatgrandfather of Mr Upton, musty documents telling of voyages in old sailing ships – dim memories of the pioneer days of the East India Company. For that Mr Upton was skipper of the East India boat Glatton in years round about 1812 and here are his ship’s logs telling of adventurous days afloat, of smuggling and greater mysteries.’

Mr Upton shows off his racing donkeys, and the article concludes with an atmospheric description of Binsted as a rural backwater.

There is no way out of Binsted except by the way you come. Binsted is a cul-de-sac, and its seclusion breathes everywhere. Rich hedgerows and silent woods are around you. There are no shops…This tree-entwined village has peace with its isolation. Roads twist in too many S-bends for there to be any need for speed limits. And few cars ever come here to churn the dust of the ancient lanes. Most of the water is drawn from the wells, oil lamps are still used. Binsted could have both modern means, I suppose, without much ado, but they prefer the old ways to the new.

The church, with its oil lamps, must be one of the tiniest in Sussex. It has a quaint air as you see it from the roadway, the thick high grass flung forward like waves by the wind, a tin cowl at the west end merrily twirling around. We went in…on the harmonium we found a bunch of sweet peas dipped in what we believe was a pint tankard. It was all so pleasantly informal. Services are not held on Sunday evenings, except on the first Sunday. Evensong, instead, is held at three o’clock. ‘It is dark here in the winter,’ I was told, ‘and the people prefer the afternoon service. We have always had it and we see no need to change.’

Rambling roses grow round the church door. And here you will find a peace broken only by the wind which sweeps through the tall grass of the churchyard, rushes on down the slopes below. So it was we finally left Binsted with happy thoughts to take us on our way; feeling just a little queer at not being, as everyone else in Binsted is, on a cycle (we saw a road worker on a tricycle), but hoping that this little Sussex village will preserve its inheritance and with its staunch ‘do nothing’ strike hand Binsted down to the generations yet to follow.

The Wisharts, by Binsted farmer and landowner Luke Wishart

In the middle 1920s my grandfather, Sir Sidney Wishart, who had been city-based and Sheriff of the City of London, decided he wanted to live in the country. My grandfather had been instrumental in the forming of what was then the insurance company General Accident, initially in Perth and then in London. He moved first from Cuckfield to Hove and then purchased Church Farm, Binsted, mainly as a country residence. He was interested in farming only as a hobby and entered animals, mainly sheep, in various local and county shows where many prizes were won. Some of these prizes still hang in the garage at Church Farm.

My grandfather was soon taken with country life and having been in the artillery naturally took up shooting on the farm. He appointed Mr Gatland as his keeper, who lived in a wooden bungalow in Wincher’s Copse deep in the woods, known as Scotland House. Mr Gatland had a son called Jim with whom I went to Walberton Primary School along with other local boys from Binsted and Walberton. During this period I spent many happy hours learning how to snare rabbit, learning how to shoot, using ferrets to catch rabbits and control vermin on the estate, as well as playing football in a team at Walberton. Summer holidays were spent building rafts on the rife and winter days toboganning down the slope next to Binsted church. After school Fred Hotston, who worked for my father at Marsh Farm, taught me how to drive a tractor, and later Reg Tutt taught me how to drive a combine.

All this was an essential introduction to my lifelong interest in and commitment to agriculture in all its forms. My grandfather died in 1938, but before this, in 1928, my father Ernest Wishart purchased Marsh Farm and moved into the house and lived there until his death in 1987. My father was a formally educated man (Rugby and Cambridge) who was expected to go into my grandfather’s insurance company. However, during his Cambridge days my father (like so many of his contemporaries) came under the influence of two causes which were to influence his whole life.

One was W.H.Hudson, the naturalist writer, who introduced him through his writing to the world of nature and especially birds. This became an enduring passion. He helped form the Sussex Wildlife Trust and purchased a farm at Sidlesham bordering Pagham Harbour in order to protect the wildlife on the Harbour. This farm was sold to West Sussex County Council on his death so that the area could be protected in perpetuity.

The second influence which affected my father at Cambridge was Communism, which he took up with enthusiasm and dedication. He saw it as a philosophy which was counter to capitalism but also as a necessary opposition to Fascism which at the time was gaining a huge following in Germany, Italy and Spain. As part of this interest he set up a company, Lawrence and Wishart, and published very left-wing books. During the Spanish Civil War he did all he could to support the anti-Fascist government and later to give aid and support to the many refugees resulting from the Franco fascist government. Later during the Second World War he gave over his London house for the Czech government in exile.

My father married my mother, Lorna, when she was 16 years old. She came from a large family (7 sisters and 2 brothers), one of whom was at Cambridge with my father and introduced them. After Cambridge my father decided on a country life and purchased Marsh Farm to be near his ageing father at Church Farm. He took up farming before the War, helped by his brother-in-law, Mavin, who had worked on a farm in Argentina. Mavin was also a Communist who had been involved in the Spanish civil war on the Republican side.

My father married my mother, Lorna, when she was 16 years old. She came from a large family (7 sisters and 2 brothers), one of whom was at Cambridge with my father and introduced them. After Cambridge my father decided on a country life and purchased Marsh Farm to be near his ageing father at Church Farm. He took up farming before the War, helped by his brother-in-law, Mavin, who had worked on a farm in Argentina. Mavin was also a Communist who had been involved in the Spanish civil war on the Republican side.My mother, largely self-taught, developed a wide circle of artistic friends through contacts in the publishing business, but also the Bloomsbury set. One of her sisters, Kathleen, was the mistress and then wife of Epstein, the sculptor; another married Roy Campbell, the Catholic poet who fought for Franco in the Spanish civil war.

My mother became a Catholic in her 50s and like many converts took up the faith with tremendous zeal. It is her faith which initiated the statue next to the pond in Binsted Park. My mother had three children. Michael, the eldest, became a painter; he died in 1997 and was buried in Binsted churchyard. I was the second son and the third child was my sister Yasmin (really a half-sister, whose natural father was the poet Laurie Lee). Yasmin married a master at Dartington Hall School and lives in Devon on a farm near Totnes.

When my grandfather came to Binsted in the middle 1920s it was a rural backwater. It had no school, no shop, no mains water or drainage, no electricity. My grandfather installed a water main for the village which supplied any house wanting to be connected. This he did with the Portsmouth Water Company (still in business). There were two cars in Binsted – his own, and one other. There had been a Sunday school held in the barn next to Oakleys Cottages, but this failed to continue. My grandfather later purchased Walberton Farm and installed Bill Ingham as a tenant and manager.

During the 1960s my father, anxious to protect Binsted Woods as a whole, purchased the wood known as Binsted Wood together with land and Binsted House from Mrs Pethers (Bill’s mother). Binsted Woods remain the largest block of ancient Sussex woodland south of the Downs and need protecting. They are managed under a rather benign regime, ‘Do little, save most’!

As to the village now, the exorbitant house prices now prevailing are detrimental to the forming of family roots in the area and this does not help in producing village cohesion. However there are occasions like the A27 bypass campaign, the Strawberry Fair, and more lately the Millennium Book project which do a great deal to bring together all the village inhabitants. Perhaps this is enough for the inhabitants of Binsted who hold to an independent spirit. Long may it last.

Isaac Rawlins: a sad tale, by John Heathcote, former Parish Clerk

This is the story of someone who lived in Binsted in the early nineteenth century – and was transported to Australia.

Isaac was convicted at Petworth Quarter Sessions on 18th November 1833 aged 48 yrs (a fairly advanced age at that time when his life expectancy would have been less than 50) of stealing ‘a piece of beech timber worth 9d’ from Ann, Dowager Countess of Newburgh and one foot of timber at 9d from John Gage and Philip Howard. The Countess is shown as being owner of at least part of Binsted Woods on 1825 maps, and the family’s arms still adorn the inn at Slindon, where she owned the estate, and had the building which is now the Folly in Eartham Wood built in 1814 as a summerhouse. The other victims of the theft were, from the name, probably connected to the Norfolk Estate.

Isaac was probably the only person from Binsted in that era whose description we have, viz: ‘5 ft 8 in tall, Stout build, Dark hair, Fresh complexion, Hazel eyes.’ He is clearly listed in both his court appearances as coming from Binsted but was almost certainly christened in Slindon, as were his four children.

He had a previous conviction (stealing 11 gallons of wheat) from 11 years before but the records do not show if this time he was starving or freezing. For that crime he had been given a seven-year transportation sentence. It was relatively unusual (and difficult) for convicts to return having completed their sentence, so he may not actually have gone for some reason. He was again sentenced to be transported to Australia for seven years, and would have been sent off to the prison hulks (probably in irons) in the Thames or Portsmouth Harbour before being taken to Van Diemen’s Land, where there were already 15,000 convicts including 1,800 women and their children.

Do you remember Magwitch in Great Expectations who had escaped from a hulk in the Thames and whose harsh sentence was transportation for life? The government policy had originally been, at the turn of the century, to empty the hulks and prisons and settle Australia before the French could do so. Captain Cook had charted the coast in 1770 and the first convict settlers and guards arrived, not knowing what to expect, in 1788 and had difficulty in staving off starvation. Because of the unpleasant history and probably the unfortunate pun in its name Van Diemen’s Land became Tasmania in its centenary year of 1856.

A four-month journey in the hold of a small wooden ship across the oceans, with minimal food and medicine, would have been sufficient punishment for Isaac’s crime in itself and worse than almost any sentence today. The contracting ship-owners were paid for the numbers of convicts leaving England rather than those landing in Australia. But as Brenda Dixon points out in her book on Walberton, the regulations protecting the voyaging convicts were stronger than those for the free emigrants. By 1833 only a small number of deaths occurred among the 300 or so prisoners on each ship as against 17% in one of the early fleets.

Living conditions in the countryside in Sussex at this time were bad following the introduction of machines. A threat to farm workers’ livelihoods (wages were 50-70p per week) was posed by the introduction of threshing machines. Riots, Luddite-style damage to machinery and rick burning were common throughout the south and south-east, inflamed by the mythical Captain Swing whose name appeared on threatening letters to unjust employers. The name ‘Swing’ came from part of the flail which was used to thresh the corn manually during winter when there was no work in the fields.

[Mike Tristram adds: There is some evidence that efforts were made to give alternative employment through job creation eg the building of the flint wall around Binsted churchyard at this time; but the wooden Mill Barn, just south of the present Binsted Nursery site, was burned down by ‘Swing’ arsonists in 1831. It was replaced on the same site, in 1834, by the flint and brick threshing barnyard, in which the Strawberry Fair is now held.]

A number of local men were transported, especially from the Westbourne-Fishbourne-Pagham area, which would have been a major corn-growing area. They were later pardoned but only about 10% returned – why should they, considering the conditions they had left?

Records of the convicts, their voyages, and what happened to them were remarkably well documented, given the conditions, the illiteracy of the prisoners and the level of penmanship of their captors, and many of them were released through a parole system and eventually freed to become successful citizens (like Magwitch).

Although Isaac Rawlins is not listed on the Tasmanian Archives web-site under the name of Isaac it must be more than coincidence that one ‘John’ Rawlins, born in the same year (1785), died without children or siblings in Tasmania in 1836 aged 51 which, given the kind of life he must have led, was a reasonable age for the time.

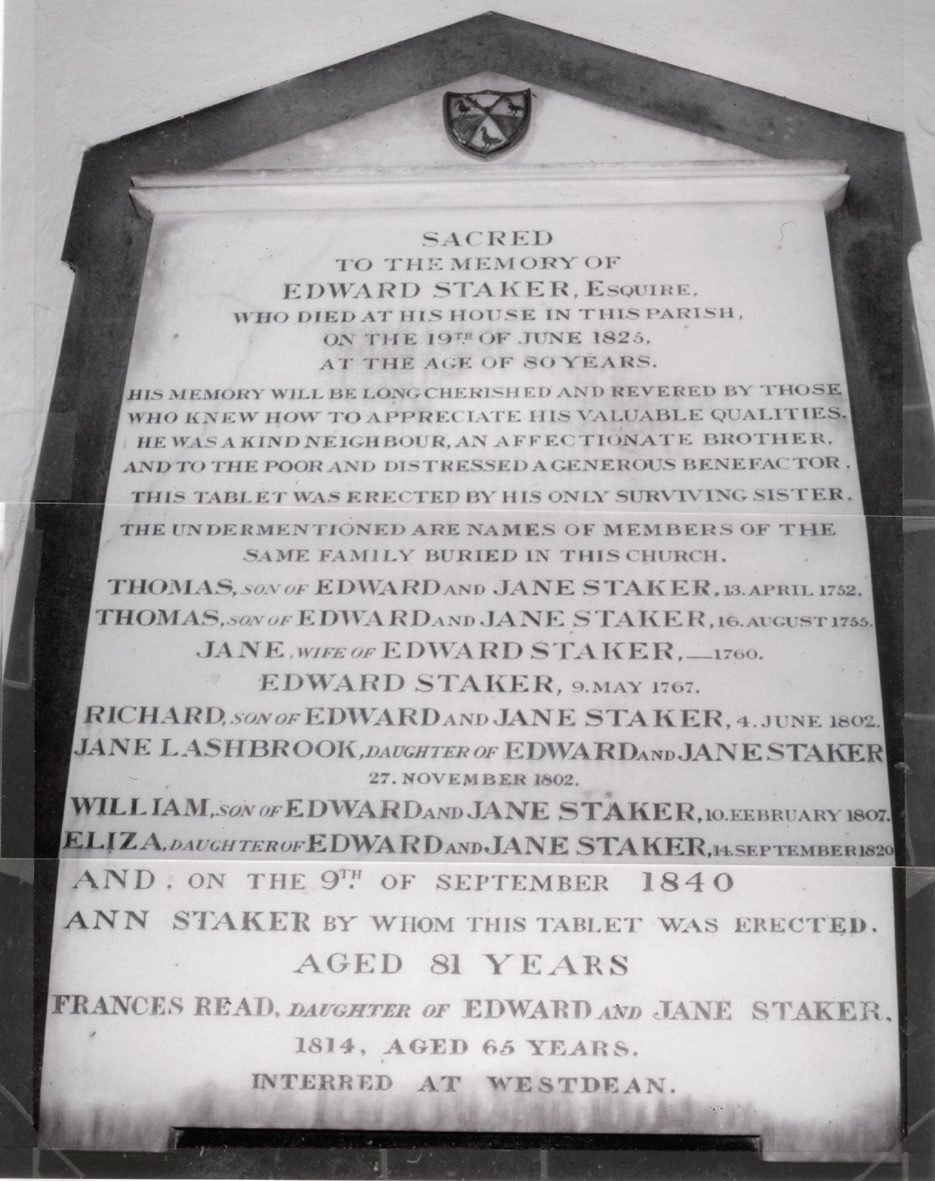

The Staker family, by Binsted farmer Brendon Staker

The Staker family, by Binsted farmer Brendon StakerIn years gone by, the Staker family was well-respected and well-known also for their generosity to the poor people of local villages. They were people of real estate, owning lands and houses in Binsted, Yapton, Climping, Ford, Tortington, Chichester, Westbourne, Aldingbourne, Southwater, Tillington and numerous other places. Two local farms still run today with the name Stakers Farm. One is in Yapton; owned by Benjamin Staker II (1785-1848), the farm was sold in 1837. The house opposite Stakers Farmhouse, now called Yew Tree Nursing Home, was built by Benjamin’s father. Both houses resemble the old Binsted House in style. The other farm is at Stakers Lane, Southwater, near Horsham. I would not be surprised if Stakers had been living in the Binsted area for a thousand years, but obviously there are no records to prove this.

Zaccheus Staker (1720-1795) married Mary Browning of Bosham in 1741, and the name Browning was then much used as a middle name for nearly 200 years. My uncle, who died in 1994, was named Lesley Browning Staker. Zaccheus’ son-in-law, William Laker, who married his daughter Anne in 1769, built Meadow Lodge Binsted, possibly for Zaccheus himself.

Zaccheus Staker (1720-1795) married Mary Browning of Bosham in 1741, and the name Browning was then much used as a middle name for nearly 200 years. My uncle, who died in 1994, was named Lesley Browning Staker. Zaccheus’ son-in-law, William Laker, who married his daughter Anne in 1769, built Meadow Lodge Binsted, possibly for Zaccheus himself.The Staker family tree, which can be found in 'Binsted and Beyond', was compiled by my great-aunt, Muriel Haynes, who was born in Walberton. According to the Stakers’ wills, Richard Staker of Yapton owned Binsted House in 1599. His eldest son Edward I (1563-1633) inherited it. It then passed to Henry I (1588-1667), then on to Edward II (1617-1673), then to Henry II (1640-1712), and on to Henry III (1675-1726). Henry III was the brother of John, my six-times-great-grandfather. From then on Binsted House was owned by distant cousins. Edward V (1718-1767) owned it, who was baptized at Binsted Church on 4 May 1718. The last male Staker to inherit Binsted House was Edward VI (1745-1825). Edward VI was a Justice of the Peace and did not marry. There were no sons to pass it on to, so it was passed on to his sister Ann (1757-1840), and the house was then inherited from her by the Read family.

People in the ‘Poor Books’

The ‘Poor Books’, or account books of the Overseers of the Poor, give us many glimpses of individuals in 18th-century Binsted. The name of Edward Staker appears very often, both as a landowner and as an Overseer.

The two earliest books preserved in the West Sussex Records Office (Par 22/30/1 and 2) cover the years 1727 to 1831; from 1759 expenditure, as well as income, is shown. In a typical year, 1754, the main landowners were Richard Alcock (paid £7.17s.6d.), the Vicarage (paid £4.7s.6d.), William Float (paid £9.9s.0d.), and Edward Staker (paid £4.7s.6d.). ‘The Lord’s Mead’ produced £2.7s.1/2d.

But more immediately interesting are the payouts to the poor. Sometimes a name or person is only mentioned once: in 1772 ‘Mary Hornsby, in want, 1s.’; the same year, ‘paid 2 shillings for the travelling woman’s child; for digging the grave, 2s.’ In 1786, ‘a pair of crutches for Ferdinand’. Sometimes the entries tell a story; in 1783 ‘Eliz. Croucher at her child’s death for bread, 2s.; watching with Croucher’s child, 2s.6d.; laying forth, 1s.6d.; paid for digging grave, 2s.; parish coffin for Croucher’s child, 6s.6d.’ (Was the travelling woman’s child buried without a coffin?)

Names appear of families recorded later, or even today; Hutsons or Hotstons (probably variations of the same name) appear regularly. (See Charles Hotston, below, and Jean Hotston’s memories in Chapter 4; she said of her husband ‘Fred was Binsted, and Binsted was Fred.’) In 1785 ‘3 Quart faggots with carriage’ for William Hotstone cost 15s.; in 1790 ‘Hutson’s Boy was sick’; in 1795 the Ruffs’ and Hutsons’ house rent was £5.4s.0d. Denyers, a name known later at Meadow Lodge, were given wood and ‘necessarys’ in 1794, and in 1795 flour and money for rent.

The date of building the poorhouse, shown in the painting by Charlotte Read and demolished by 1910, is not recorded. But in 1777 there is an entry ‘to posts and nails for the poor house and carriage, 10s.6d.’ In 1778 ‘paid Mr Allcock for half a year’s interest for money the parishioners hired [this word is unclear] to build the poor house, £1.2s.6d.’ In 1779 ‘to the digging a well at the poor house, £2.2s.0d.’ Before the new poorhouse was built (perhaps about 1777), a poorhouse was rented, costing £2 or £3 a year. References to renting a poorhouse continue to 1787.

The date of building the poorhouse, shown in the painting by Charlotte Read and demolished by 1910, is not recorded. But in 1777 there is an entry ‘to posts and nails for the poor house and carriage, 10s.6d.’ In 1778 ‘paid Mr Allcock for half a year’s interest for money the parishioners hired [this word is unclear] to build the poor house, £1.2s.6d.’ In 1779 ‘to the digging a well at the poor house, £2.2s.0d.’ Before the new poorhouse was built (perhaps about 1777), a poorhouse was rented, costing £2 or £3 a year. References to renting a poorhouse continue to 1787.Other entries record work done; in 1759 ‘paid Caigers [still a name to conjure with in Yapton] for picking 41 L of stones, £1.0s.6d.’; ‘paid Richard Tupper for work done at the Common gate, 2s.6d.’ The many entries for pairs of pattens suggest the perennial muddiness of Binsted’s lanes – more extreme in those days, as witnessed by the entry in 1761, ‘to a tree to lay across the lane, 2s.’

The Reads of Binsted House

Ann Staker died in 1840 without children, and left Binsted House together with much of Binsted (and Stakers Farm at Southwater, Horsham) to Harry Read, the son of her elder sister Frances Read. Harry farmed at West Dean and did not take up residence at Binsted. However he implemented protracted renovations to the property, starting in 1840. These were not completed until the year after his death in 1848. In 1849 (on completion of the renovations) his son William Henry Read (1822-1888), who was known as ‘the 8th Squire’, married Sarah Walburn (1823-1907) and moved into Binsted House.

Wednesday July 13th, 1898, at Binsted Rectory near Arundel, Sussex: wedding of Charles Read of Binsted House and Florence Lewis of the Rectory. Florence wrote the caption: ‘Left to right, standing: Mr. C. Green, Leslie Lewis, Helen Miller, Edwin Ellis, Kathleen Lewis, Minnie Read, Mansel Lewis, Judy Lewis, Edgar Lewis, Doug Read, Mrs. Graburn, Dr.Green, Mrs Izard, Mitchell Ellis, Rev Izard, Uncle Ned Miller, Mabel Lewis with Vivien Lewis (baby), George Tanner. Left to right, sitting: Mother, Annie Read, Edie Lewis, Norah Lewis, Bridegroom and Bride (CER and FMCR), Ted Read, Fan Read, Mrs Crowley, Miss Hollis, Father, Newton Lewis, Emily Lewis, William Read.’

Remarkably, some vivid personal memories of this family have survived to the present day.

The link was an interview in 1994 with Henry Pethers of Binsted (1914-1996). Henry Pethers had come to Binsted in 1928 when his family took over the Black Horse pub. They also ran a shop and bakery, and had run the London and County Stores in Walberton for four years. The family had moved from London in 1924, when Henry was ten, to help his mother get over the death of her daughter Doris.

In 1939 Mr Pethers married Margaret Ernestine Read, known as Kitty, born in 1899. She was the only child of the marriage in 1898 between Charles Ernest Read, youngest of eight children of the William and Sarah Read of Binsted House, and Florence Lewis, one of thirteen children of the Rector of Binsted, Henry Lewis (1830-1907). The wedding is captured in a splendid group photograph taken on the Rectory Lawn by the Rev. Lewis’s son Henry.

Mrs Pethers’ memory of her grandmother, Sarah Read, was that she ‘sailed like a barge’ in her vast bombazine dresses and ‘never did anything’. Sarah’s sister, Hannah, had lost all her money and came to live at Binsted House as a ‘lady’s companion’ and much-valued aunt. William and Sarah had four sons and four daughters. They were Charlotte or Lottie; Annie, Fanny and Minnie; Edward Staker, William or Wig, Harry or Doug, and Charles Ernest (Mrs Pethers’ father). The Staker name was customarily used by the eldest son in the family.

Edward Staker Read, Mrs Pethers’ ‘Uncle Ted’, was known as ‘the Squire’ or ‘the 9th Squire’, and lived at Binsted House after his father’s death in 1888. He was known as ‘Edward Staker’. Like his father, he was a JP. He used to say that his father, William Henry, once saw poachers, chased them with his gun, firing and reloading as he went, stopped them and caught them, took them to Arundel and charged them himself. His gun was a muzzleloader, made in Arundel. ‘You had to look out when ramming powder and shot down, as the muzzle would cut you. The muzzles were made out of horseshoe nails, often called ‘Damascus steel’. There was a walnut tree up at the house – all old houses had one; when your eldest son was born a sapling was planted, and when he was twenty-one a gun was made with walnut wood from the tree for the butt.’

‘Uncle Ted’ (1857-1924) lived the life of a squire and kept a hunter and groom. The groom’s name was Styles; he lived at Morley’s Croft and was paid a pension until he died. ‘Some of the housemaids that were venturesome used to get up at four in the morning and bribe the grooms to let them ride the hunters.’ The other boys were all apprenticed to someone; there was ‘string-pulling even in those days’. Doug went into the tea business in Mincing Lane. It was possible to commute to London – you walked through the woods to Ford Station. Wig disgraced himself (he had a drink problem) and was ‘rusticated down in the country. He spent most of his time in the harness room. It was a nice room and never leaked, and was well locked up.’ He helped run the farms on the estate.

A nice insight into Edward Staker Read and his knowledge of bees comes from the diary of Laurence Graburn, a local farmer, passed on via his daughter to Clifford Blakey of Havenwood Park. Mr Graburn wrote:

Mr E.S.Read of Binsted was a great bee-man and had as many as 110 stocks in the wood adjourning his house. As a young man he worked in the Bank of England, but when 21 was sent home in galloping consumption, this did not kill him, and though never robust he lived to 67. I met him on horseback once riding through Arundel to the Station, he told me I am going to do a thing I have never done before, viz: I am going to order a truck for a ton of honey. This sounds a lot but it was a honey year and would only be a portion of his takings that summer.

I saw Mr Read do the smartest thing I ever saw, he had imported some Italian Queens as an experiment and when I went there one day he showed me a very strong stock he expected to swarm, he had introduced an Italian Queen into it. After watching it for a while we went into lunch, leaving his man to keep an eye on them, we had not been there long when the man came to say they had swarmed and were going away, neither Mr Read nor his man were very agile so I ran out and was able to follow them for a while, but could not keep up. The last I saw of them they were flying towards Dick Denyer’s house [Meadow Lodge]. I searched this with no result when I met Mr Read just arriving, we then saw Denyer very excited, who told us a huge swarm had settled in a Plum tree in his garden. Mr Read assured him they were his bees, but Denyer would not part as he had kept bees before and his sisters wanted him to start again. We then watched Denyer take them, and as often happens a few returned to the bough, Mr Read looked at the little cluster and quickly picked one off and put it in a match box, he had the Italian Queen and in a few seconds the air was full of bees again, and Mr Read told Denyer he would have to take them again, but they would not stay as he had the Queen in his pocket. The bees not finding the Queen returned to their old hive, and Denyer very upset at losing them.

Charles Ernest Read (1862-1939) went into Denny’s bacon firm in London as a clerk in the office. During the First World War, women went into munitions and then into office jobs, and clerks were sacked, including him. ‘He was very much against women taking men’s jobs.’ He lived at Penge near Crystal Palace in London. Later, after his marriage to Florence Lewis, with her dowry they took a boarding house at Dalgeny Mount near Ventnor in the Isle of Wight. There was a constant stream of visitors coming for holidays, so well-known to the family that ‘to me they sounded more like relatives’.

Charles insisted on calling Mr Pethers Harry, not Henry. ‘He didn’t agree with Uncle Henry, so I was called Harry, like it or lump it. I remember him saying of someone that he was a very short man, but he himself was 18 inches shorter than me. He didn’t think he was short. No short man ever thinks he’s short; just other people are too bloody long!’

‘Miss Lottie’ and her sisters

Miss Lottie, or Charlotte Sarah Read (1850-1943), known by Mrs Pethers as ‘Aunt Tot’, was the oldest of the family and used to say she should have had the property. ‘If you see one of the servants running with her apron over her head, crying her eyes out, she’s just met Miss Lottie. They say she used to put on a man’s hat and do the flues.’ In old age she lost all her hair and was bed-ridden. ‘She used to sit up in bed and bang her stick and give orders. I never saw Miss Lottie and I don’t think I missed much.’ However, she did some notable paintings of Binsted, and ensured her place in local history by making a drawing of the interior of Binsted Church as it was before the ‘Restoration’ in 1868 – box pews, gallery, grinding organ and all. Her obituary gave a kinder picture of her.

‘Nothing made her more happy than to talk of the times she had enjoyed in the old house, with its beautiful park and woodlands, and of the walks and picnics with her brothers and sisters in the neighbouring district…Her love of animals remained with her, and a few hours before her death a black cat, which she called her ‘boon companion’, was to be seen on her bed. Miss Read remembered the times when labour was very cheap. Women would work for 6d. a day in the house and the average labourer’s wage was 12s. a week. Messages and carriage of parcels were paid for by drinks of good ale, then to be bought for 8d. a gallon…Although bedridden for over 12 years, she was always cheerful and patient…She much admired the writings of Dean Inge, and she would chat upon his teaching most readily…No terrors of modern warfare could frighten this fine old lady as she lay serenely in her quiet room. Those who knew her will long remember with affection her quick humour, kindly disposition, and sincerity’: another way of describing bluntness and a sharp tongue.

Annie, or Anna Maria Read, died in 1900 aged 46. She was a great gardener, and it was thought she got cancer from it. Miss Fanny ‘went a bit funny’ as a girl and spent some time in an asylum. She was deaf (apparently deafness ran in the family), and spoke in an odd way, but was musical and used to play the organ in Binsted Church. She used to bang on the door of the church, or on the Rectory door, and ask to speak to ‘William’ (Drury, the Rector). She was a problem to look after, always in trouble for breaking things. Her care was a big expense to the family, and ‘pulled them down’. ‘You’d lose sight of her and she’d be gone, out of the front door. You’d go after her and find one galosh in the lane.’ Her mental problems continued. ‘When Miss Fanny poked her umbrella through the window pane in her bedroom I got up a ladder and mended it. She poked the panes out on purpose; she thought I was Mr Upton (Sid Upton, who farmed at Marsh Farm) or his ghost. He had auburn hair, the same as mine was before it went grey. Though what Mr Upton was doing up a ladder mending a window I don’t know. As fast as I mended the pane she would poke her umbrella through another one.’

The eccentricities of the three old ladies, and perhaps the black cat, may have been the genesis of a Binsted myth. Paul Wyatt, whose family farmed in Walberton, remembers that in the 1930s his father rented land at Binsted Park as pasture for heifers and some sheep. ‘Behind the house was a stable yard with some loose boxes, which we used occasionally for sick heifers. The first time my brother and I went into this yard we saw three ‘witches’ brooms’ leaning against a wall. This made a good story to tell at the next mealtime. We rarely saw the sisters, but when we did they were always dressed in black, with little showing except their hands. After a few years one of them died and we noticed soon afterwards that one of the brooms had gone. That didn’t wait long for an opportunity at the meal-table.’ This must have been Miss Fanny, who died in 1936, aged 83. Minnie died in 1939, aged 75.

Binsted House

Binsted House has now been demolished. After the First World War, there was a decline in income from the land, so that the Read family had to sell off property in order to live. There was no money to repair the house, and Charles Read and his wife Florence built a new house, the Manor House, nearby in 1924. Ralph Ellis, a noted sign-painter, painted Binsted House in a ruinous state in the 1940s, overgrown with creepers and with glass missing from the windows. The handsome stables, and the ruins of the house, remained until about 2000. They have since been replaced by a large new house on the site.

As part of the planning permission, excavations were done in August 2000, which established ‘with some degree of certainty that the core of the house was an L-shaped building of late 17th or early 18th century date, added to in several stages in the 18th and 19th centuries, with a service range of c. 1800. The separate flint-built stables and coach house were…mid-19th-century in date, not 17th-century as suggested in 1998’ (letter from John Mills, County Archaeologist). They were made with re-used older bricks. Counting the rings of an oak which grew by the ha-ha, blown down in 1987, gave a date of 1760-1770 for the ha-ha, which divided the garden from the pasture or field and kept livestock out without spoiling the view.

According to an archaeological survey of the ruins in 1998, a map of 1778 (Yeakell and Gardner) shows the house enclosed in a large rectangle, surrounded to the north, south and west by woodland, with an east vista giving a clear view to the river Arun. A track which has now disappeared ran north-south through the woodland west of the house. By 1825 the woodland to the south had largely been cleared and the southern and western vistas of the Park opened up. Windows on the east side had been blocked, perhaps because of the window tax introduced in 1745, while those on the south side were left. This enabled enjoyment of a new view and gave full benefit of the sun.

Mrs Pethers remembered being told that the imposing ‘false front’ had been added to the house in the eighteenth century, giving it a carriage sweep and a porticoed doorway with windows on either side – actually French windows opening like doors, facing away from Binsted Lane and onto the Park. Mr Pethers remembered: ‘As you entered the hall you saw stairs rising in front of you then turning right at a landing. At the turn of the stairs was the only lavatory in the house. Over the hallway was a glass dome that let light into the hall.’ This may have been the feature behind stories of a ‘minstrel’s gallery’. ‘All work on the house was done by local tradesmen from Arundel, who came on penny-farthing bicycles, or estate workers. The work was crude and rough – there was no beautiful furniture. It was a well-known fact that horses were better looked after than human beings.’

The two main front rooms on either side of the hall were the drawing-room and the dining-room. Over each was a bedroom: one Miss Lottie’s and one Miss Fanny’s. ‘Old Miss Lottie didn’t like men. She wouldn’t have allowed me there in any case. So I didn’t go into the bedrooms.’ There was a still room under the stairs to the left of the hall, and opposite on the right was the nursery. In front of you was a door to the cellar. The nursery had its own door to the outside, to the nursery lawn on the right hand side of the house.

On the left, past the still room, was a huge scullery. It had a water pump and Mr Pethers used to pump up water for the old ladies. There were stone sinks and a back door to the dairy, a single-storey room with thick slate worktops where butter was made with milk from the cows. Opposite the dairy was the bakery, with an oven in the corner, and tacked on the end was a harness room.

Beyond the ‘nursery lawn’ was a glasshouse. There was a hatch into the coal cellar (which was above ground) from Binsted Lane, with a hook in the wall for the coalman’s horse to be attached to.

There were small upstairs rooms for servants at the back of the house, poky and oddshaped, with sloping ceilings. There were back stairs leading to a passageway – these stairs were not safe to walk up in Mrs Pethers’ time. Another small staircase led from one servant’s bedroom to an attic. ‘That’s where the scullery maid was pushed. She was the first to get up in the morning and give everybody tea.’

Outside there were granary stones, a cider press in the ‘hovels’ or open-fronted sheds in the courtyard, ‘pigsties’, and a garden off to the left. ‘They were going to wall it all the way round, but they ran out of money.’ There was a summerhouse, a beehouse on the lawn, a pond garden, and three ponds (the middle one still exists as the ‘Madonna pond’). The toilets and drains all drained into the ‘Pond garden’ under the road.

There were wells ‘all over the show’ (though only two were found in the excavations). Mr Pethers used to draw two buckets of water from the well at the side of the house for the two old ladies. At that time people often thought the water was bad; if two or three children died, they blamed the water. ‘Well’s bad. Just lost mother and granny don’t look so good. Need a new well.’ They would dig a new well, near the old one, and often did not bother to fill the old one in. One well at Binsted House had rusty water: it was so brown that when one of the boys was a baby people used to think he had ‘khaki napkins’. The northernmost of the three ponds always had rusty water and was known as ‘the iron-bound pond’.

Bill Pethers, the son of Henry Pethers and Margaret Read, added the following rider to this account of the Read family and his father’s memories: I think my father only saw my great-aunts in their final years and remembered them as old and lonely ladies. My late mother, being that much older (15 years) than my father, often related her fond memories of her aunts, who she said were both kind and caring people, who loved music, painting and the countryside. I remember from my childhood the drawing room at the front of the house had an upright piano in it and several violins and piles of music. I am sure that my mother inherited these attributes from the Read side of the family. My grandfather, Charles Read, whom I never met, was described as a kind and courteous gentleman, with a good sense of humour, who made welcome all who obeyed the rules of the countryside. If you worked for the Reads you were not well paid, but you were respected and cared for like one of the family.

If the Read family had a failing, it was their naivety in the fast and changing world around them, that was so different from the peace and isolation of Binsted Park. They were, after all, born in a different age, now almost forgotten.

Jane Caseley’s letters

Jane Caseley, born Laker, was for seven years housekeeper to her aunt Ann Staker at Binsted House, before she died in 1840. Jane left Binsted for the USA in 1844. In 1870 and 1888 she wrote to William Henry Read from Knightstown, Indiana. Her first letter thanks him for his kindness to her husband, Mr Caseley, who had been visiting Binsted, and continues: ‘He thought as almost everyone does that Binsted is one of the most delightful spots he ever saw. The holly he brought I planted in a box. I think it will grow. I hold it almost sacred. The leaves of the carnation I have pressed in a book to preserve them, the sight of which brings to my mind many recollections of past joys and sorrows. Binsted is the place where I spent the longest time of my life; although a disinterested person I cannot help feeling attached to it. The changes are great indeed, but not more so than I might expect. It is twenty-seven years since I left. But really which seems to surprise me the most is yourself having a family of eight children! It appears as almost yesterday when you was only a small boy, and used to run around fishing and other amusements, and sometimes you used to get hungry and ask me for something to eat when you did not want your Aunt Nancy to see you. The last

recollection is you were a young Gent just left school, and going on visits to Mr Palmer…did you ever get your silk cradle quilt Mrs Johnson of Yapton was to make for you? If so you have some pieces of my dress in it. I was truly happy to learn you enjoys Binsted so much, and I sincerely hope many blessings may attend you and yours.’

In 1888 she wrote again, to thank William Henry Read for sending a photograph of Binsted House – perhaps one of the ones we have, taken by Henry Lewis, son of the Rector. ‘On our return home, your kind remembrance of me and happy greeting in the sight of the dear old place Binsted House; I cannot express how grateful it is to my feelings to know you have not forgotten me. Please accept my best thanks. I could scarcely stop from viewing, it all looked so natural, the old cherry tree still there, and everything around appears so beautiful. I think I can recognise the old pigeon house peering through the evergreens, and harmless sheep grazing. But what a pleasing addition, I thought, had yourself and family been standing on the green, where the sheep looks so large that I could have had a look at you. However, the view as it is looks beautiful. Mr Caseley tells me he believes my eyesight is benefited by looking at it so much.’

Of his eight children, she writes: ‘But the little ones then I trust are all grown up, with the elder ones in love and a great comfort to their parents. Such is life and the changes which naturally takes place.’ In fact, none of the four girls married, and only two of the boys. The only child of the eight was Mrs Pethers, daughter of Charles Ernest. Jane Caseley continues: ‘I have to tell you of one of our American wonders. Have you heard of our finding natural gas, by going down into the bowels of the earth for it? This winter we have been supplied with natural gas for all cooking and heating purposes as well as the rooms lighted.’ She explains how it is found by boring eight or twelve hundred feet below ground: ‘As soon as they find it they ‘shoot the well’ as they call it with some combustibles, when up comes the gas in a full flame of light which can be seen many miles around, till it is confined and conducted into pipes to supply the town.’

A third letter from her which exists was addressed to Sarah Read, and was probably sent after the death of William Henry Read in 1888, as a result of Sarah asking for information about the Staker family. Jane Caseley comments on the lives and deaths of Ann Staker’s nine brothers and sisters and remembers the burial of ‘Aunt Nancy’ (Ann Staker) in the vault in the chancel of Binsted church in 1840. ‘I looked in the Sunday after her funeral and saw it was not very deep.’

The Lewises of the Rectory

The Lewis family at the Rectory had no money problems, even with thirteen children. Henry Lewis, the Rector, who built the Rectory in the 1860s, had in 1856 married an heiress, Edith Miller. He changed his name, Bones, to Lewis in 1869. Their daughters had a dowry of £7,000 each. Florence, their fourth child, Mrs Pethers’ mother, ‘always used to think she married beneath her in marrying the Squire’s son from Binsted House,’ remembered Mr Pethers. ‘She always used to ram in the Rectory – wonderful Rectory – wonderful Father and Mother.’ She wore her hair in the ‘Princess Alexandra style’, with extra hair she used to pad in. ‘Women are judged by their legs now; in those days it was by the amount of hair they had. There was yards and yards of horsehair in their buns.’ In many photos Florence is wearing beautiful lacy blouses, hats and jewellery.

There was intense competition within this large family. ‘The rows that went on! The hair that was pulled out!’ One area of competition was who had the best garden. Each year a big box of seeds was sent for, and vegetable seeds were handed out to the brothers-in-law to grow in their gardens. Among the sisters, ‘If X wrote to Y saying something unflattering about Z (such as “She’s put on a lot of weight lately”) Y might well write to Z and enclose the unflattering letter from X’. But one of the boys, known as ‘darling Leslie’, had an angelic face and curls. His space in the linen press with a named space for each child was named ‘Darling Leslie’.

On 23 August 1908, a purse of money and a beautifully written citation were presented to Mr and Mrs Stephen Kent, of Kent’s cottage in Binsted Park, on their Golden Wedding day by the parishioners of Binsted. Seventy-six people are listed as having ‘much pleasure in presenting you with the accompanying Purse as a small token of our esteem and regard on the occasion of your Golden Wedding, and in appreciation of the excellent manner in which you (Mr Kent) have carried out your duties of Parish Clerk during a period of 39 years.’

Many Reads and Lewises are named, also Mr and Mrs Alfred Hotston, and Mr Alfred Hotston Junior. Another contributor was Mr Richard B. Denyer or Dickie Denyer of Meadow Lodge, mentioned above. He and his sister farmed at Meadow Lodge for over 60 years and were remembered fondly in the Women’s Institute scrapbook of 1947. J.Mansell wrote: ‘Their wisdom, their humour and the beauty of these wonderful old people cannot be described…I shall never forget seeing Miss Denyer coming home in deep snow one morning after an all-night vigil by an old lady’s beside. She was exhausted, and yet for a whole winter she repeated that labour of love, and I think very few people knew of it.’

Dickie Denyer is also remembered by Paul Wyatt of Walberton. ‘He was a tall, dignified old man who was always charming and polite to everyone, and that included his few cows which he used to watch over as they grazed beside the road. When his cows had had their fill of the grass beside the road, he escorted them back to his paddock or to the cow-house. He rarely let his cows graze near to the Park gate but if one of them ever did, it provoked Mr. Read to wrath and he was quickly on the warpath. Mr. Read took his dignified politeness for submission.’

Harold Dean and the Great War, by Beryl House

In 1830 Charles Hotston (Charles I) was baptised in Binsted. He had eleven children; one of them, Emma (1866-1950), married Henry Dean, and their son Harold Dean (1894-1929) had a daughter, now Beryl House (b. 1923), who has written about her family and in particular her grandmother Emma.

According to church records, Charles I, Emma’s father, was born in 1830 at Binsted, the son of James Hudston and his wife Harriet. James Hudston was born in 1795 and the Binsted records name his father as being one William Hudson, born in 1753, who in turn possibly could have been the son of one Thomas Husher or Usher and his wife Mary; but the ancient records are hard to decipher and not very explicit. The gradual change in the surname was probably because the persons concerned could neither read nor write and the only clerk was probably the incumbent who wrote down the names phonetically in an effort to keep a record. If the subjects had thick country accents, not easily understood, these could have resulted in the gradual change of name.

Charles Hotston was landlord of the ‘Sir George Thomas’ Arms’ (or ‘the Spur’) at Slindon for 52 years. [The present landlords of Binsted’s Black Horse pub, Clive and Victoria Smith, formerly were landlords at the Spur – Ed.] Whilst also a wood merchant he no doubt used the abundant wood growing in the area as well as at nearby Binsted from where he had originated. Binsted Woods in my early days were let out by their owner(s) for rent to be coppiced and husbanded correctly. The tenant sold the woody produce of his hard labours as logs for fires cut from large branches, bean poles from long straight sticks and faggots made from brushwood tips. Nothing was wasted and after coppicing the resultant new growth could be used all over again and again in eleven year cycles. Faggots were in great demand for pea sticks as well as for kindling for fires and in bakers’ ovens. The faggots, or bundles, [called ‘bunts’ by Binsted resident John North who had worked at tying them in his childhood in Cheriton - ed], were burnt in the long ovens, which had a regulated draught and were vented at the far end to remove the smoke. Then the ashes were raked out forwards and the loaves inserted on a long spatula in their place. The resulting loaf was delicious as the crust had absorbed the taste of the burnt wood – something which has never been simulated by any other later method of baking.

After her marriage to Henry Dean on 1st February 1893, Emma continued her duties at the pub and they both lived there. Their first child, Harold, my father, was born in the third bedroom from the left on 19th September, 1894. He was apparently a very bright child and when he was only three years old he was sent to school in the village. On the first day he attended Emma walked with him across the fields from the pub. However, he refused to let her meet him afterwards and insisted on returning home by himself. Emma was worried so watched out for him from the pub and was greatly relieved to see him coming in the distance. She dared not let him see her but went forward to meet him at the very last moment. He was in great form and thrilled by his achievement.

Emma watched her children grow up to become responsible citizens. Harold worked hard to become a fully qualified electrical and mechanical engineer while Lena was apprenticed to millinery. Absorbed by all of the then modern techniques Harold installed a simple form of electricity in the family home. At that time Littlehampton was not served with electricity but there was coal gas which their house used for lighting and some of the cooking in an early black cast iron gas stove. During the colder months the kitchener stove took care of all cooking and heating of the kitchen. Harold’s electrical system provided light only and was run by a small petrol engine mounted on a huge stone block in the garden shed. The stone was large enough to allow a big fly-wheel, which was about the diameter of a large bicycle wheel and which projected out over the side of it, to revolve when the engine was going. It was run for a short time each day and the electricity produced was stored in a large accumulator in readiness for being drawn upon when the lights were used in the house.

It was on the 3rd August, 1914, and just before Harold’s 20th birthday, that disaster struck when England and Germany commenced hostilities. The Great War of 1914-1918 had begun. Along with most of his friends Harold joined up and went to war, leaving his mother in charge of the electrical arrangements. Daily she faithfully set it going and when he returned home for leave from France he saw that it was maintained until eventually it had to be given up and the house reverted back to the exclusive use of gas.

During his army service in France Harold was in the Royal Ordnance Corps and became an ‘artificer’, that is ‘a soldier mechanic’, attached to the ordnance, artillery and engineer service. He was skilled in sending and receiving messages in both semaphore and Morse codes. He rode a horse and with others was responsible for the movement of the big guns which in those days were horse-drawn on special carriages. Pitted by shell holes, the muddy terrain of Northern France during the terrible trench warfare was extremely treacherous, and Harold’s horse slipped, threw him and then rolled on him, breaking his leg. This accident brought about a spell in hospital back in England or ‘Blighty’ as it was known to the soldiers. While in hospital the walking patients wore bright blue uniforms which they also called ‘Blighty’. Wearing wet clothes and sleeping in damp blankets in France brought on an attack of pleurisy which meant another spell of ‘Blighty’. Eventually he recovered, but it left what was called a ‘spot’ on his lung.

After the Great War ended on 11th November, 1918, Harold was eventually demobilised from the army in 1919, but not before he had won a number of trophies for rifle shooting. These were two silver plated tankards, awarded to ‘Corporal Dean, Nov. 6 1918’, when after hospitalisation he was transferred to No. 1 Reserve Motor Transport Depot, Grove Park, and again to ‘Sergeant Dean, Feb. 1919’. He later won six silver teaspoons, singly, after joining the Miniature Rifle Club Society. He was disappointed that the pretty delicate design of the first two was changed so that all six were not alike. He had great accuracy, became a ‘crack shot’ and his exploits entitled him to shoot at Bisley.

Emma was very proud of him and was delighted when he married May Burch in 1920. She was devastated by his untimely death in 1929, from tuberculosis, when I was only just six years old. She took great comfort from the fact that his last resting place was in Littlehampton cemetery which she could easily visit.